The four tonne, eight metre long lumbering behemoth rattled and shook along the heavily corrugated wide sandy track. I held the wheel and tried desperately to find smooth patches. This usually looked like swerving my way across either side of the road and some of the time finding solace in driving off the road entirely. Maree was thirty kilometres behind me and the driving was intense. My average speed was twenty kilometres per hour and frustration was building.

The van and I made it to a dip where a small salt lake had formed. The road smoothed out. I pulled over, took a large breath, and went for a walk. As I was crunching my way over the salted ground I looked up and noticed another traveller had stopped behind me. They were letting more air out of their tyres. I took the inspiration to do the same and got going again. Since the tyres had much less pressure now, almost half of the standard, the journey was relatively smoother – I could almost do fourty. Only six hundred klicks remaining.

After some time, the corrugations ceased and I had a cinematic expression of freedom, driving fast, the side of the van in the mirror with a long plume of curling brown dust trailing behind me, a boyish grin on my face. I felt the oppression of corrugation as a distant memory and began to idealise the rest of the journey – smooth sailing, no problems. Of course, you know that not too long after this mental architecture did the corrugations return. With teeth shaking, I disassembled the internal building and accepted the truth of the unknown.

In the back of the van, I have cutlery, crockery, bottles, jars, hard things, soft things – every possession providing for a life – and everything rattled. A cacophony of jingles, bumps, and squeaks. Sometimes when the road got really rough, things would loose themselves from their storage areas and I would see a rain of items in the rear view mirror.

After a few hours of the bumpy/smooth/bumpy/smooth procession I came across a desert oasis named Coward Springs. Date palms lined the road in and a hand painted sign stood among many labelling a natural spring spa. I ate dates and sat in the deep mineral spa chatting to a few other travelers.

Ever onward until my body became weary. There was an abandoned railway building up ahead. I turned into the entrance, drove past (to my surprise) a dam full of water, and nestled the van among a copse of trees. As the sun was going down, I took a walk. This was a waystation for the old Ghan railway, hand built from local stone and I supposed near a spring that fed the full dam. A brown rusted square metal tank stood on a corroding frame and beyond that, endless landscape to the horizon. I felt peaceful here and returned to the van for a meal and rest.

The next morning, I walked toward the horizon I saw yesterday. The ground was made of rocks, not quite small enough to be sand, and not quite big enough to be obstacles. My feet sunk a little with each step. There was nothing to compact this ground over the years and the surface layer had a distinct fluff to it as I slowly crunched my way to nowhere.

I found myself at a solitary tree and loitered. Far in the distance I could see the white van through the trees. It was tiny. I absolutely adore the distance of vision in this land. Besides the van among its scattered community of ruins there was clear desert view for three hundred and sixty degrees.

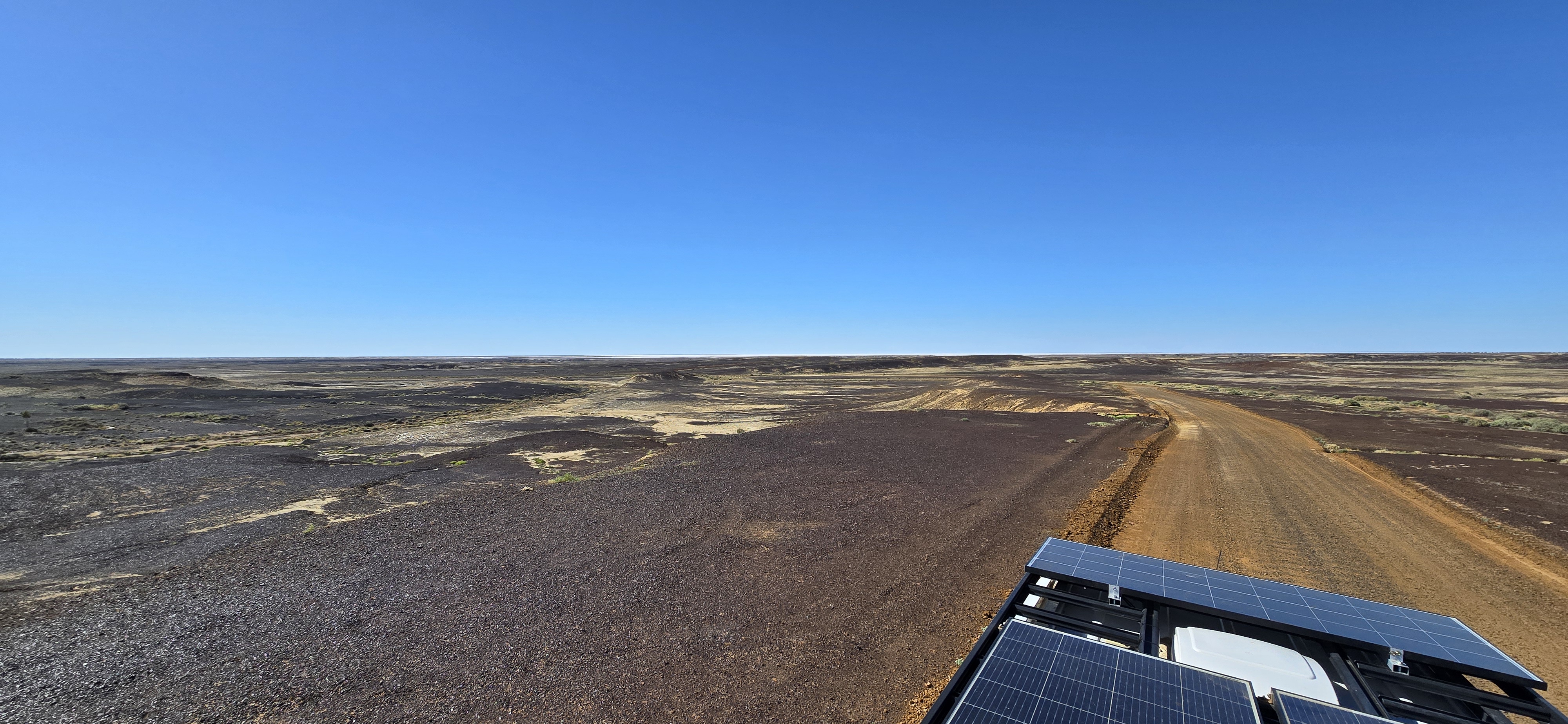

Kati-Thanda, or Lake Eyre, was to my north and I wanted to stay overnight. There was a turnoff before William Creek, so I took it. Only sixty kilometres, but at my pace through the corrugation it would take over an hour. After a pleasant patch of smooth road, the van and I climbed a hill and at the top, the entire landscape changed.

My jaw dropped and I absently took my foot off the gas to stop at the side of the graded road. From my vantage point I could see without end, countless peaks and valleys of black rolling hills. Low black mesas dotted the horizon with shadowed striations from rain erosion. I got out and picked up a rock, a dense glazed product of volcanic activity. As I tossed the rock back it made a metallic clink and the world returned to the silent whoosh of wind.

The drive turned into an exquisite tour of this slow undulating black landscape, a path cut through the underworld. I drove onward.

As if to contrast this shaded beauty, the perfectly flat, sub sea level salt lake of Kati-Thanda emerged from the end of the hills. I stopped at the end of the track and walked out onto the lake.

The afternoon sky was mostly covered by a haze of cloud. My gaze took in the majesty of formlessness. Where the horizon of the lake ended, a mild straight-line shimmer existed before the appearance of cloud, there was hardly a break between the white of the salt and the white of the sky. After the sun began to set behind the lake and I, this horizon glowed subtle peach and cobalt hues. I took some dead grass and shrub from the coastline, had a small fire a few hundred metres from the shore, and played my drum until nightfall.

Discover more from Life on four wheels

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment